New battery safety regulations concerning thermal runaway have prompted an evolution in pack design

In 2020, the Chinese government issued GB 38031, a new national safety standard for electric vehicles. It set a new requirement for vehicle safety in which passengers must receive at least a five-minute warning to exit the vehicle if a battery thermal runaway event is detected. Earlier this year, a revised standard was issued, which tightened those safety requirements considerably. While the five-minute egress rule still stands, the standard is now more prescriptive around failure modes, testing, documentation and performance.

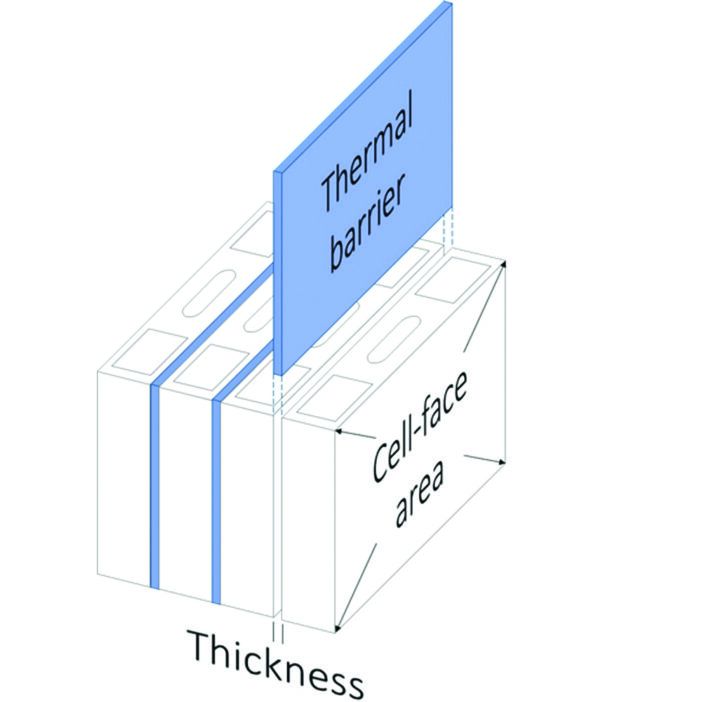

Thermal barriers are one of the key technologies required to meet this standard. In pouch- or prismatic designs, thermal barriers are typically placed between each cell to serve as a firewall. If one cell goes into thermal runaway, thermal barriers cut off the cell-to-cell conduction that is the first pathway for thermal energy to travel. Thermal barriers cannot stop the spark, but that can delay or prevent it from lighting the fuse. While GB 38031-2025 does not explicitly require thermal barriers, it is now much harder to comply with the standard without them.

At the same time, EV batteries are getting bigger. Higher energy densities, tighter packaging, and shorter design cycles mean there’s less room — literally and figuratively — for error. To prevent a single-cell thermal runaway from propagating into adjacent cells, designers need to pack as much thermal resistance as possible into the tiny gaps between cells. But how much is necessary?

It turns out there is a simple proportionality between the energy content of the cells, the cell-face area, and the critical thermal resistance of the thermal barrier. That proportionality can be found by conducting multiple thermal runaway tests in which thermal barriers of varying thickness are trapped between two cells in an open-air environment. By triggering one cell into thermal runaway and monitoring whether the other cell follows it, two populations can be identified: propagating and non-propagating designs. These populations are separated by a boundary denoting the critical thermal resistance below which thermal propagation will occur.

This analysis shows that thicker, more energetic cells require extra thermal resistance to prevent propagation by cell-to-cell heat transfer. When the same type of testing is conducted on NMC cells, a similar linear boundary exists but with a taller slope. Due to their lower trigger- and higher peak-temperatures during runaway, NMC designs can require 50-60% more insulation for a pack of the same energy capacity.

Aspen Aerogels’ engineers have an in-depth understanding of the complex mechanisms of thermal runaway. They design PyroThin cell-to-cell barriers with a system-level approach to not only tackle thermal propagation but also sustain cell health and performance throughout the pack’s lifecycle.